Who Should Own the Earth?

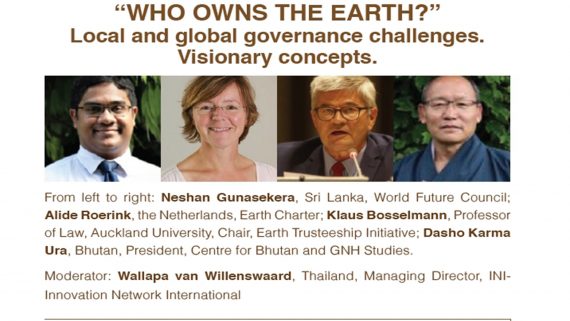

Below is the keynote speech ’Who Should Own the Earth?’ by Dasho Dr Karma Ura at the Earth Trusteeship Forum, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok.

The Earth Trusteeship Platform offers open, decentralized, ‘multi-polar’ and independent creative space for persons and organisations motivated to exploring Earth Trusteeship as an innovative principle of governance and local and international law, able to match the challenges of the 21st century and the wellbeing of future generations.

Who Should Own the Earth?

Keynote Address by Dasho Karma Ura, Ph D.

Earth Trusteeship Forum, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, Thailand.

The author Peter Barnes raised a penetrating question with his book Who Should Own the Sky (2007). Although we would assume that the sky over our head is owned equally by all of mankind, Barnes suggested that it was owned more by those who used the skies and polluted them more, at the expense of others who do not pollute as much.

The sky over head was also a major political-ecological theme in the European elections in the 1960’s. In 1961, German Chancellor Willy Brandt, a Nobel Laureate, campaigned that “The sky above the Ruhr has to become blue again.”

Today, the sky above most urban spaces look duller, hotter and dirtier, and is almost certainly used and ‘owned’ more by polluters.

The question ‘Who Should Own the Earth?’ is an all-encompassing topic relevant to policy makers, legislators, businesses, academics and technologists, to name but a few. The question is a poignant one precisely because of the rapidly increasing rate of environmental destruction; the present generation is posing a grave threat to future generations through its current political systems and concepts.

In that sense, our generation are adversaries of future generations, rather than their allies, and custodians or trustees of the earth’s resources. And as we received the world’s resources in a better state than we pass them on, our ancestors were trustees of nature, which we so heavily rely on.

The first obvious answer to Who Should Own the Earth? is that it can and should be owned by all those future generations who will be born in the future. If all beings yet to be born own it, it should logically follow that it is equally owned by beings in the present and the past. Naturally, in sheer terms of relevance, this applies more to present and the future generations. But the power of decision- making is abrogated by the present generation, simply because future generations cannot take part in the decision-making process. If future generations equally own the Earth, they also have a right to be considered in current-day decision making. Our policies and politics need to be able to consider, and make space in our decision-making frameworks, for their voice and their agency.

Current decision-making processes, however, only favour current generations. It is a short-termism that lack clarity when it comes to how we view the future, as its stretches further and further in time. We lack the ability to measure and understand the impact of our decisions on other human beings and sentient beings.

I would go do far as to say that these frameworks are extremely poor or non-existent. The Nobel Laureate Amartya Sen (1961, 1967) is amongst the leading pioneers who have explored the idea of value over time. Social Discount Rates (Karbowski, 2016) or SDR’s are a critical element in cost-benefit analysis when the costs and the benefits differ in their distribution over time. Lower discount rates favour future generations, but it is unclear how low it should be. Rates that are closer to the value of zero will give equal weight to both future generations and the present.

Environmentalist and conservationist-oriented decision makers prefer low discounting rates to be adopted. In a survey of about 200 experts, 75% recommended that a social discount rate of 2% (Drupp et al, 2015) be used. But many current commercial valuation methods use higher discounting rate for infrastructure investments or other assets, thus embedding a bias against future generations.

The second answer to ‘Who Should Own the Earth?’ is that it ought to be owned at every point of time in history by all sentient beings who share the basic preference to live well and happily, whether they be animals or human beings.

As Buddha said, “All that moves on earth are supported by the Earth.” In other words, all that moves on the earth should receive equitable support from the Earth’s resources. Increasingly, however, use of the Earth’s resources is not equitable, whether we consider that in terms of conventional material means such as income and assets, or experiential outcomes of wellbeing and happiness such as psychological wellbeing, ecological resilience, community vitality or balanced time-use in everyday life.

By having a more in depth and holistic system to measure experiential outcomes as well as material means, people in Bhutan should, in course of time, attain a maximum level of happiness and wellbeing that is sustainable for future generations. By managing 52% of the land in Bhutan as protected nature reserves, Bhutan has created a carbon well and protected biodiversity for other sentient beings to fare reasonably well.

The choice of intergenerational resource allocation can be based on various rules such as discounting methods, or legislative-constitutional provisions. Discounting based on market logic, however, does not offer long-term guidance for intergenerational equity. The constitution and legislation is therefore an additional recourse to help define the parameters for intergenerational equity.

In the case of Bhutan, ‘environment’ is defined in the broadest sense of the term, so that it can be entrusted to every Bhutanese citizen for preservation. The Constitution of Bhutan, written under the leadership of our kings, has certain provisions and institutional structures favourable to forest and biological preservation.

For example, the Bhutanese Constitution prescribes a minimum of 60% forest cover. Bhutan currently has 72% forest cover. The country is presently carbon negative.

“Greenhouse Gas emissions will exceed carbon sink after 2030 in business as usual scenario. In the carbon neutral scenario, Bhutan can remain carbon neutral at least until 2050” (Kei Gomi et al, 2019).

Although the Constitution of Bhutan is explicit in terms of forest ratio, it does not specify other resource bases for intergenerational equity, besides saying that Bhutan should “ensure sustainable use of natural resources and maintain intergenerational equity.”

The third answer to ‘Who Should Own the Earth?’ is a traditional-historical Bhutanese one. Traditional Bhutanese beliefs say that mountains, for example, are owned by local Mountain Deities. The current inhabitants in a territory are only transient occupants and users.

In psychoanalytic terms, mountain deities are the personification nature; rivers, clouds, rainfall, snowfall, weather, forests, wildlife and all their other ineffable interrelations are personified by deities. If the Earth is owned by Mountain Deities, who personify nature, then vital parts of nature have rights on their own, like a person.

Human being’s property rights cannot be extended over Nature’s resources, or rivers and springs, just as it would be odd for us claim ownership over clouds and mist. At the most, they can be common to the locality and accessed equally by its inhabitants who are seen more as stewards of the resources they need.

Bhutan has of yet been unable to give explicit rights to any parts of nature, such as legal rights of rivers or mountains, to be undisturbed, in the way Thomas Berry conceptually established in 2001. Traditionally, however, the climbing of a set of snow peaks was not accepted, because they are regarded as the abode of Mountain Deities.

The concept of rights of a place or a natural phenomenon such as a river or mountain, seems to have been recognised traditionally. Bhutanese believed, and most still believe, that lakes- or river-beings (mtsho smanmo, bla tsho) dwell in such water bodies. Sensitive micro-ecologies such as cliffs, marshes, and rich groves are also considered the abodes (gnas khang) of earth deities (gnas bdag zhi bdag) and thus were off limits to be exploited by people.

Unfortunately, the legal rights of Nature’s elements have yet to find its place in modern laws such as the Forest and Nature Conservation Act, Environment Assessment Act, or Biodiversity Act.

The fourth answer to ‘Who Should Own the Earth?’ is that in the contemporary period, in principle, the earth is owned through agreements and laws within and among nations. Part of our collective inheritance, such as air quality, internet connectivity, oceans, or space and so forth are managed within and among nations through regulations, treaties and agreements. States or governments are managers of the great commons of the earth. They are not owners. Owners, as I stated earlier, are all sentient beings of the Earth, who themselves are reproduced in a cycle of birth, death and, perhaps, rebirth, according to Buddhism.

An important endeavor for all states and governments is to think of their afterlife, or legacy, i.e. what we do today has an impact on the infinite future, as opposed to the brevity of present tenures, and we need to help bring birth to policies and laws that listen intently to the voices from the future, through an awakening induced by both science, and the non-dual imagination and compassion of a Bodhisattva, who is here to relieve suffering for all beings.

The fifth answer to ‘Who Should Own the Earth?ä is that, in terms of political economy, the Earth has been increasingly owned and used by the market, commercial corporations, and the owners of capital. Although all human beings have equal right to the Earth’s three principle resources in terms of source, sink and services, in reality, the polluters, commercial-exploiters and capitalists have hijacked the Earth’s resources.

The rights of labour, the rights to common properties, the rights of the community, which depends on the commons, and the intrinsic value of Nature to exist, have all been diminished respectively by the rights of capitalists, the rights to private properties and the rights of individuals. The rise of market has also led to the abolition of non-market exchange of labour that is a crucial aspect of social support and solidarity.

Corporate and private rights have been privileged increasingly over the rights to the Commons. In an evolutionary context, the inhabitants of the earth have thrived so far because of the richness and abundance of the Commons from which all sentient beings drew. But the great Commons of the earth are being over-exploited on the one hand, and over polluted with toxicities on the other. Corporate and private rights have also, to a lesser extent, been privileged over the rights of the vast majority of human beings and other sentient beings.

An 18th century mural of Zhabdrung Ngawang Namgyal (1594-1651), considered to be the architect of Bhutan.

In his biography, the monk-founder of Bhutan, Zhabdrung, made an astonishing statement. He wrote that the animals found in Bhutan, like elephants, bears and rhinos, are Bodhisattvas existing to lead all beings to enlightenment, instead of the other way around.

He saw formations of clouds over mountain peaks, and stunning natural beauty and described them in terms of wondrous spiritual symbols. A sense of beauty of nature penetrated him completely, and he was able to see the earth itself as the beginning and end of aesthetic wellbeing.

It seems that these concepts are as valuable today as they ever were and might offer us a way to recover the Earth’s abundance as source of wellbeing for present and future generations.

Keynote speakers at the Earth Trusteeship Forum event